The following article was written by Erb Institute Faculty Director Tom Lyon and Corporate Political Responsibility Taskforce Director Elizabeth Doty. This article originally appeared on the Network for Business Sustainability website. Read the original article here.

Many say that businesses can help solve the world’s problems. Grand challenges like climate change, poverty, and biodiversity loss can benefit from business resources and insights.

That might be true. But businesses can’t be sure that they’re truly part of the solution unless they examine their political activities.

Businesses have a powerful influence on politics. They help determine government priorities, the content of laws and regulations, who gets elected and how the public views issues. They lobby, issue public statements, join coalitions, and influence employees’ political engagement.

Businesses, and business executives, are also a significant source of money in politics. In the United States, for example, they account for roughly 60% of political contributions and fuel some of the largest “dark money” groups.

Businesses’ political power can advance sustainability. For example, in 2018, US businesses pressured the US government to uphold its Paris climate commitment. But too often, businesses work against climate and other sustainability issues politically. They have lobbied against sustainability action, sometimes through trade association activities, and even fostered disinformation.

The Limits of Corporate Social Responsibility

The fact is, many businesses don’t consider their political actions as part of their sustainability strategy. Typically, companies emphasize Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), focusing on philanthropy or on operational improvements like increasing efficiency. A firm practicing CSR this way might become incrementally greener — but also oppose the environmental policies needed to solve society’s challenges at scale.

We want to change this pattern. We’re founders of the Corporate Political Responsibility Taskforce (CPRT), based at the Erb Institute at the University of Michigan. The CPRT is a working group of business leaders, supported by researchers and other stakeholders. Our focus is identifying what it means for companies to engage responsibly in the political sphere. After all, they influence our economy, our civic institutions, and the living systems on which we all depend.

Here, we answer key questions for any company that wants to use its political clout responsibly.

What is Corporate Political Responsibility?

Recently in Israel, many companies spoke out publicly in opposition to the legislature’s proposed radical weakening of the powers of the Supreme Court. Hundreds of executives and investors signed a letter calling on the government to protect democratic institutions.

That’s an example of Corporate Political Responsibility (CPR).

CPR refers to the idea that companies have an obligation to engage in politics responsibly, including sometimes staying out. Responsible engagement means considering their own broader interests and their obligations to society.

In practice, CPR includes:

- ensuring they have a legitimate basis for any engagement

- making sure a company’s political activities align with their commitments to employees, customers, investors and other stakeholders

- ensuring their activities are transparent

using their political clout to protect and support the systems on which we all depend, including our economic system, our civic institutions and our natural environment.

4 Principles for Corporate Political Responsibility

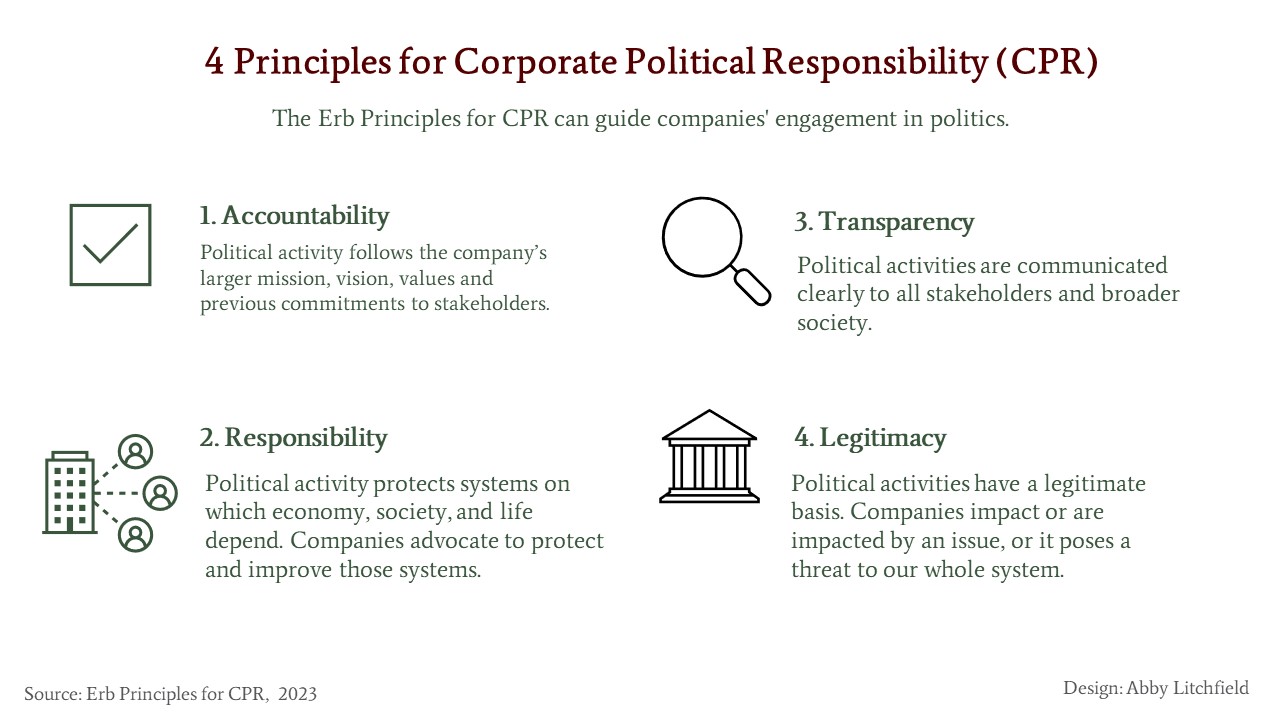

Working with our Corporate Political Responsibility Taskforce, we crafted the Erb Principles for Corporate Political Responsibility, officially launched on March 7, 2023. These are an actionable, non-partisan template that companies can use to decide whether and how to engage in political influence.

There are four principles or guidelines.

-

Accountability. Accountability means aligning a company’s political activity with its key commitments, including its purpose, values, stated goals and promises to stakeholders. This is critical for integrity and stakeholder trust. Otherwise the activity will be seen as hypocrisy, greenwashing, insincerity or poor governance.

But accountability alone won’t make a company responsible. What if a company’s values, and political affairs, focused solely on maximizing short-term shareholder value without regard for societal impacts? Acting to block climate legislation might align with that company’s values. But we would consider it irresponsible if it refuses to preserve a livable climate for future generations.

-

Responsibility. We argue that companies have an obligation to consider their impact on the systems on which our economy, society and life itself depend. At a minimum, this means doing nothing to harm those systems. It should also involve stepping up to advocate for preserving and improving those systems. For example: companies can actively advocate for effective climate regulations, rather than just sitting on the sidelines while the planet burns up.

-

Transparency. Transparency means communicating openly so stakeholders and the broader society know you are being accountable and responsible. Transparency means complete communication to stakeholders about the company’s full set of political engagements, including participation in trade associations.

-

Legitimacy. This means ensuring the company has a legitimate basis for using its resources and voice. Legitimacy addresses whether the firm has a morally and ethically sound basis for engagement on an issue. Companies can have a role in a particular issue because they have contributed to it, it affects their business or stakeholder commitments, or it is of such consequence that it affects our entire system. (More details in next section.)

A more detailed statement of the Principles can be downloaded from our website.

When Should Companies Get Involved in Political Issues?

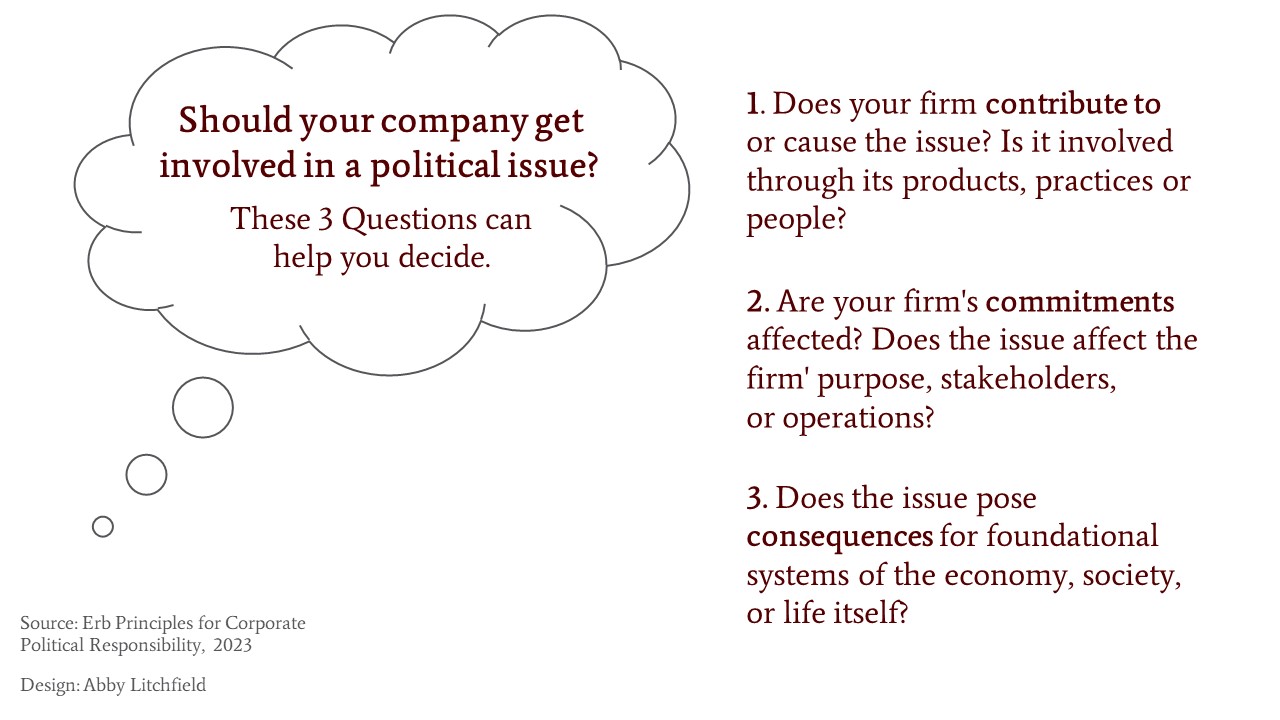

Let’s talk more about legitimacy: When companies have a good reason to get involved.

Business leaders are naturally suspicious when outsiders tell them they need to take action on issues that go beyond their core business. Neither do they want to impose their views on civil society. Yet these same leaders are also committed to acting responsibly in the face of real threats.

Our experience suggests three criteria for assessing whether it is legitimate for companies to get politically involved on a given issue:

-

Contribution, which refers to whether the firm has caused or contributed to the issue or is involved through its products, practices or people;

-

Commitments, which refers to whether the issue affects the firm or its business, has a material impact on key stakeholders, or relates to its purpose or commitments; and

-

Consequence, which refers to situations where the issue represents a threat to the foundational systems on which the economy, society or life depend — and the company has the capability to help.

If any one of these conditions is met, then a company has a legitimate rationale for being involved politically, and the more conditions met the more powerful the rationale for involvement.

Are these easy decisions or evaluations?

Not necessarily. As companies consider whether to get involved, one of the biggest challenges is recognizing when “Consequence” (the 3rd criterion) applies. When are “foundational systems” actually threatened?

There are real threats to the systems and institutions that underpin successful markets and societies. These systems and institutions include a healthy planet, open and diverse civic discourse, fair market rules, and well-functioning, trusted civic institutions.

Historical examples show that business is critical in upholding these systems and institutions when they are at risk. In South Africa under apartheid, business groups visited exiled leaders, brokered meetings with the government, joined religious groups in opposing violence, supported negotiations to end apartheid and helped manage disruptions during the first free elections. By contrast, in Chile in 1973, business collaborated with a brutal military dictatorship that overthrew a 150-year-old democracy.

So, the stakes are high. We draw on ideas of sustainability and “democratic capitalism” to emphasize four foundational systems that businesses should uphold. These are:

- Healthy market rules of the game: Policies, regulations, and tax codes that create a playing field for business and align private interests with the public good

- Healthy civic institutions: Constitutional democracy, the rule of law, civic freedoms, and fundamental human rights

- Healthy civic discourse: Ways for citizens to participate meaningfully in public life

- Healthy natural systems and societal resources, including human and physical capital

Yet, that doesn’t mean that businesses should get involved in every issue. There are difficult questions and conflicts that should be debated by civil society, without solutions imposed by unelected corporate officers.

In the end, whether to get involved is a question of conscience, which should be guided by diverse perspectives, humility and judgment. It’s also a topic for continued learning; consider connecting with Erb’s Corporate Political Responsibility Taskforce to discuss such issues with peers and experts.

How to Make the Case for Corporate Political Responsibility

We’ve talked about businesses’ power and influence, and about what businesses should do.

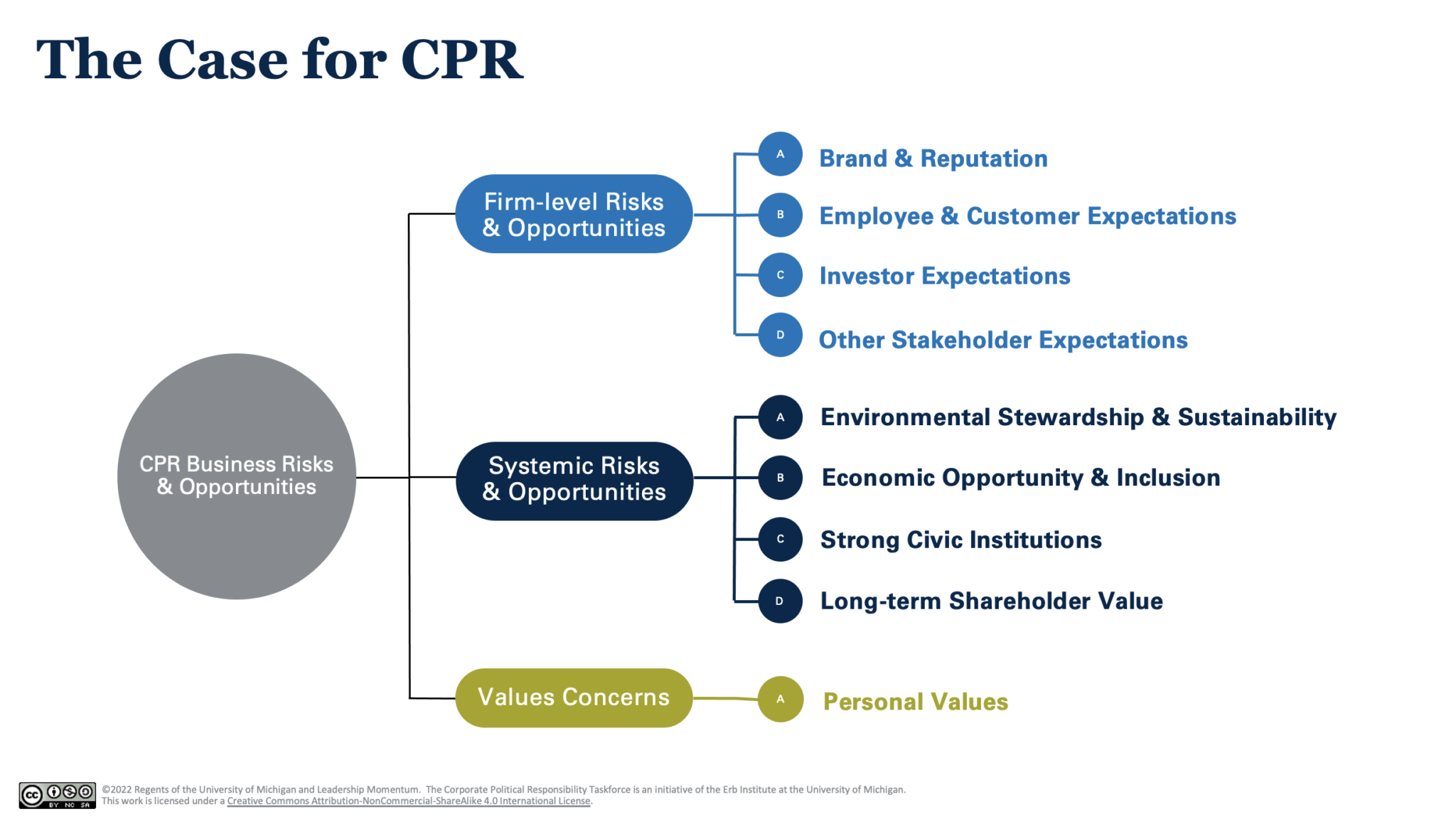

How can you make the case for more attention to your company’s political activity? Our graphic below provides 3 types of rationale.

-

Reduced risks to brands. Consider how employees (or potential employees) feel when their company is in the headlines for lobbying in ways that contradict its sustainability commitments. Many stakeholders – including employees, customers, investors and executives – see CPR as a moral imperative. That’s especially true among younger generations.

-

Reduced systemic risks. Unmanaged environmental damage, climate change, and political polarization lead to chaos and uncertainty. They complicate the business environment – as we’ve seen recently with another disruption, the pandemic.

-

Values concerns. Business is the most trusted institution internationally, according to the Edelman Trust Barometer. People look to businesses for leadership. And all businesses have a role – for example, small businesses are more trusted than big business in the United States.

CPR can also reinforce trust in government. That trust is falling – partly due to actions by business. “Lobbying is central to dwindling faith in government,” notes a report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Given all of these impacts, we believe leaders have a shared interest in CPR, as a key lever in shaping a long-term political environment that enables firms to prosper.

Why to Start with the Erb Principles

There are many global and US-based frameworks that touch on corporate political influence. We think the Erb Principles are the best, in part because they draw upon other frameworks intentionally and respond to recent debates.

Here are some of the other frameworks: the Center for Political Accountability’s Model Code of Conduct for Political Spending, Sustainable Development Goal 16, OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, Transparency International’s principles, the World Benchmarking Alliance’s Core Social Indicator CSI-18, GRI’s Standard 415 on Public Policy, and the UN Guiding Principles on Human Rights (UNGPHR).

Consider starting with the Erb Principles because:

- The Erb Principles are more comprehensive. Most of the other frameworks emphasize Transparency, with some attention to alignment (or Accountability in our terms). Few have outlined Responsibility, though several describe not using influence in ways that undermine the public interest. Almost none have outlined Legitimacy in our way, though we drew on the UNGPHR as inspiration for our three criteria.

- The Erb Principles are also more adaptable. Because multinational companies operate in multiple countries, we have crafted relatively simple and general principles that can be tailored for specific regions.

- The Erb Principles were hammered out by a group of business executives deeply familiar with today’s political issues, in collaboration with academic experts and non-profit leaders. The Principles offer companies a place to stand in the face of powerful swirling political winds, a principled and non-partisan basis for formulating corporate political strategies – including staying out of certain issues altogether.

Bring the Erb Principles to Your Company

We are happy for you to share the Principles with corporate leaders within your organization. Our website has many resources to help you in this process, including a video series of Expert Dialogues. You can even join the CPRT, and gain access to other corporate leaders and a network of experts, research, tools and supportive groups. Submit an inquiry at the bottom of this page and we will follow up.

Find Out More

Lyon, T. et al. 2018. CSR Needs CPR: Corporate Sustainability and Politics. California Management Review 60(4)

Corporate Political Responsibility Taskforce Homepage

Winston, A., Doty, E., & Lyon, T. 2022. The Importance of Corporate Political Responsibility, MIT Sloan Management Review

Dolan, E. 2023. How – and When – Should Companies Engage in the Political Process? Harvard Business Review

Marquis, C. 2023. How A Framework For Corporate Political Responsibility Can Enhance Business Social And Environmental Sustainability. Forbes