Another Believer, CC BY-SA , Jennifer Weeks, The Conversation

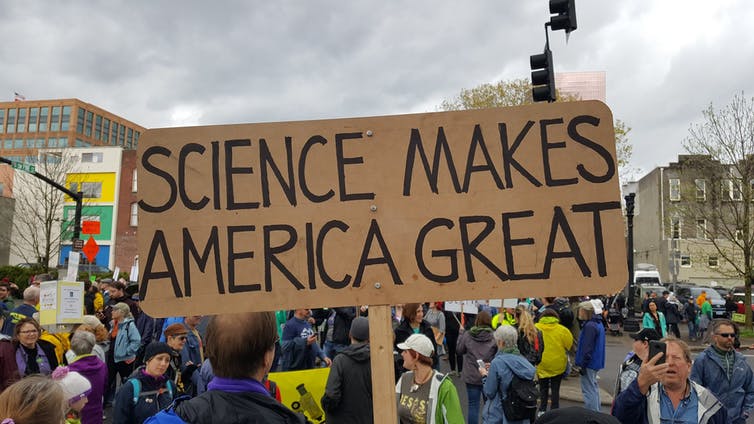

Scientists and environmental advocates will be speaking out this month about the Trump administration and what they view as its abuses of science. This year’s March for Science on Saturday, April 14, has a goal of holding leaders accountable for “developing and enacting evidence-based policy.”

Earth Day, which falls on Sunday, April 22 this year, is approaching its 50th anniversary and has become a global event. Although many Earth Day events will focus on issues – such as this year’s theme, plastic pollution – the Trump administration’s efforts to roll back environmental regulation will also loom large.

These articles from our archives provide some examples to support charges that the Trump administration is politicizing science on climate change and other environmental issues to drive an anti-regulatory agenda.

1. Restricting information

Across many federal agencies, information about climate change and policies to address it has been removed from the internet or archived in hard-to-access locations. Terms like “climate change” have been removed from agency websites, and others have been renamed. For example, the Department of Energy’s Clean Energy Investment Center is now simply the Energy Investor Center.

Morgan Currie, a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University’s Digital Civil Society Lab, and Britt S. Paris, a Ph.D. student in information studies at UCLA, acknowledge that public information on government activities changes to reflect the policy directives of different administrations. But as they note, climate change is still occurring, whether it is reported or not:

“In our view, burying climate science diminishes our democracy. It denies the average citizen the information necessary to make informed decisions, and fuels the flames of rhetoric that denies consensus-based science.”

AP Photo/Andrew Harnik

2. Stacking advisory panels

Many scientists provide advice without pay to federal agencies on issues within their areas of expertise. But the Trump administration has downgraded or eliminated independent scientific input on a number of key issues.

For example, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt has barred scientists receiving agency grants from serving on EPA advisory committees, and has replaced a number of academic board members with representative of industries and state governments.

Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke has created a new advisory board on recreation that is heavily weighted toward industry and another on international wildlife protection made up mainly of trophy hunters.

Past administrations that tried to stack advisory boards ultimately failed to achieve their goals, according to Donald Boesch, a professor of marine science at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science who has served on many federal advisory committees. Other scientists, not affiliated with the administration, will call out biased conclusions and unsupported recommendations from these slanted panels, Boesch predicts:

“Consequently, policies and regulations based on the panels’ recommendations will be less likely to withstand public or political scrutiny and be more open to legal challenges than if they were based on more balanced input.”

DOI, CC BY-SA

3. Manufacturing controversy

Although his proposal was ultimately rejected by the White House, EPA administrator Pruitt campaigned energetically in 2017 for a “red team-blue team” review of current climate science. Such an exercise, Pruitt asserted, would provide fresh perspective.

Critics viewed this idea as an attempt to undercut a widely supported consensus that human actions are changing Earth’s climate, by putting climate deniers on an equal footing with mainstream experts.

Red team-blue team exercises center on “the spirit of challenge by an antagonist,” explains University of Michigan climate scientist Richard Rood, who has participated in these types of reviews. Rather than shedding light on serious scientific questions, Rood describes Pruitt’s proposal as a performance designed to advance a political agenda:

“Such spectacle will be based on emotional appeal and will rely on manipulating the message about the role that uncertainty plays in scientific investigation. The goal will be the amplification and persistence of public doubt – a goal that would be undoubtedly achieved.”

4. Distorting scientific findings

Many statements about climate change by Trump administration officials have questioned whether climate change is occurring or have downplayed the need to take action. Most recently, in late March 2018, EPA staffers received a list of “talking points” about climate change that instructed them to emphasize uncertainty when discussing the issue with local communities and Native American tribes.

For example, one point stated:

“Human activity impacts our changing climate in some manner. The ability to measure with precision the degree and extent of that impact, and what to do about it, are subject to continuing debate and dialogue.”

Joe Arvai, a professor of sustainable enterprise at the University of Michigan who served on EPA’s Chartered Science Advisory Board from 2011 to 2017, calls this framing an exaggeration of uncertainties around the human causes of climate change. “In effect, Pruitt is asking EPA staffers to lie,” Arvai contends.

In another area – the health impacts of exposure to pollutants and toxics – Pruitt has proposed to change EPA policy so that the agency would only consider scientific research if underlying raw data can be made public for external scientists and organizations to review. Pruitt says this approach will increase transparency, but Arvai argues otherwise:

![]() “[I]n reality, this rule would mean that critical public health studies could no longer be used to inform EPA policy because some of the data are protected by doctor-patient or researcher-participant confidentiality.”

“[I]n reality, this rule would mean that critical public health studies could no longer be used to inform EPA policy because some of the data are protected by doctor-patient or researcher-participant confidentiality.”

Jennifer Weeks, Environment + Energy Editor, The Conversation

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.